Purple Alert - Case Study

Using service design approaches in designing the purple alert system

In 2015 the Innovations & Development Team at Alzheimer Scotland was approached by our Chief Executive Henry Simmons to see how we could better support missing people with dementia in Scotland.

We couldn’t have predicted that the outcome of that open brief led to the development of a pioneering, multifaceted project which has impacted communities across Scotland and it became a point of reference nationally and internationally, within missing persons organisations.

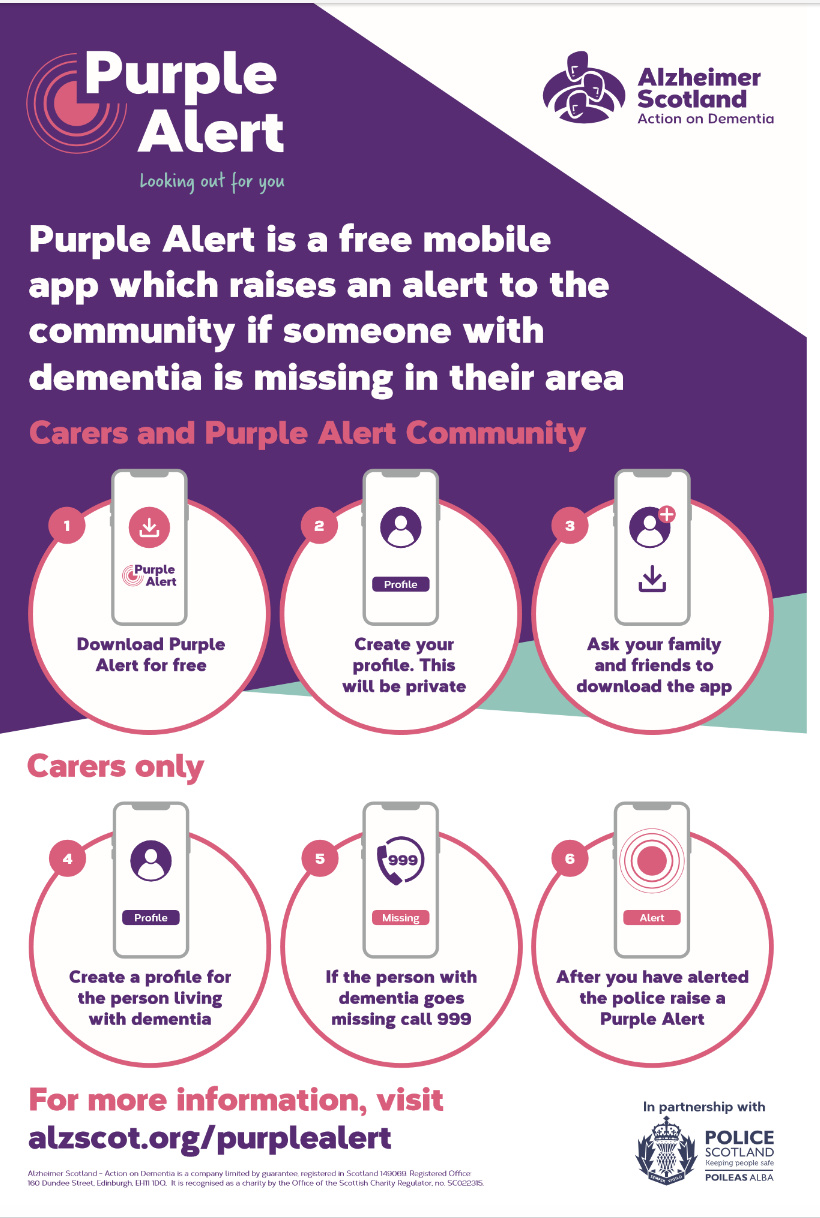

Purple Alert is an app, but not just an app. It’s an interconnecting network of services, people, communities, tools, organisations with the common goal of making people with dementia safer when they’re out and about. Purple Alert continues to evolve according to new technologies, new policies, emerging community trends, but at its core it will always be a person centred service.

Photo by Vishnu Prasad

Writing the briefing

Writing a clear brief is pivotal in keeping the work on track.

Developing a new product/service will take at least 12 to 18 months and having a brief you can refer back to over time prevents the service to mutate into something else over time.

The ‘5 W’s and H’ are a good starting point for breaking down the brief:

- What is it and what does it do?

- Who uses it? Where is it used?

- When is it used?

- Why is used?

- How is it used?

It’s good practice referring back to the brief, but it’s not sacrilegious tweaking it if you realise some parts are irrelevant/ outdated/ need changing over the design process. It’s always good practice prioritising brief items in clusters: what it must do, what it should do and what to could do. Then if you have to compromise, you know where to look.

There are many ‘product design specifications’ templates online, pick the relevant specifications to your service and customise it to your requirements

Prototype, test, break. Repeat

When we concurred that an app would have been the most obvious product to develop, we wrote the brief in much more details, to understand what the app should do, why, how, when and for who. We ‘rapid prototyped’ everything, systematically, for months. We always involved our original steering group in executive decisions to make sure we wouldn’t lose our user centred approach. Most importantly, we weren’t afraid to ‘break’ prototypes. In fact we were actively sabotaging them, to reveal weak spots at an early stage

Rapid prototyping

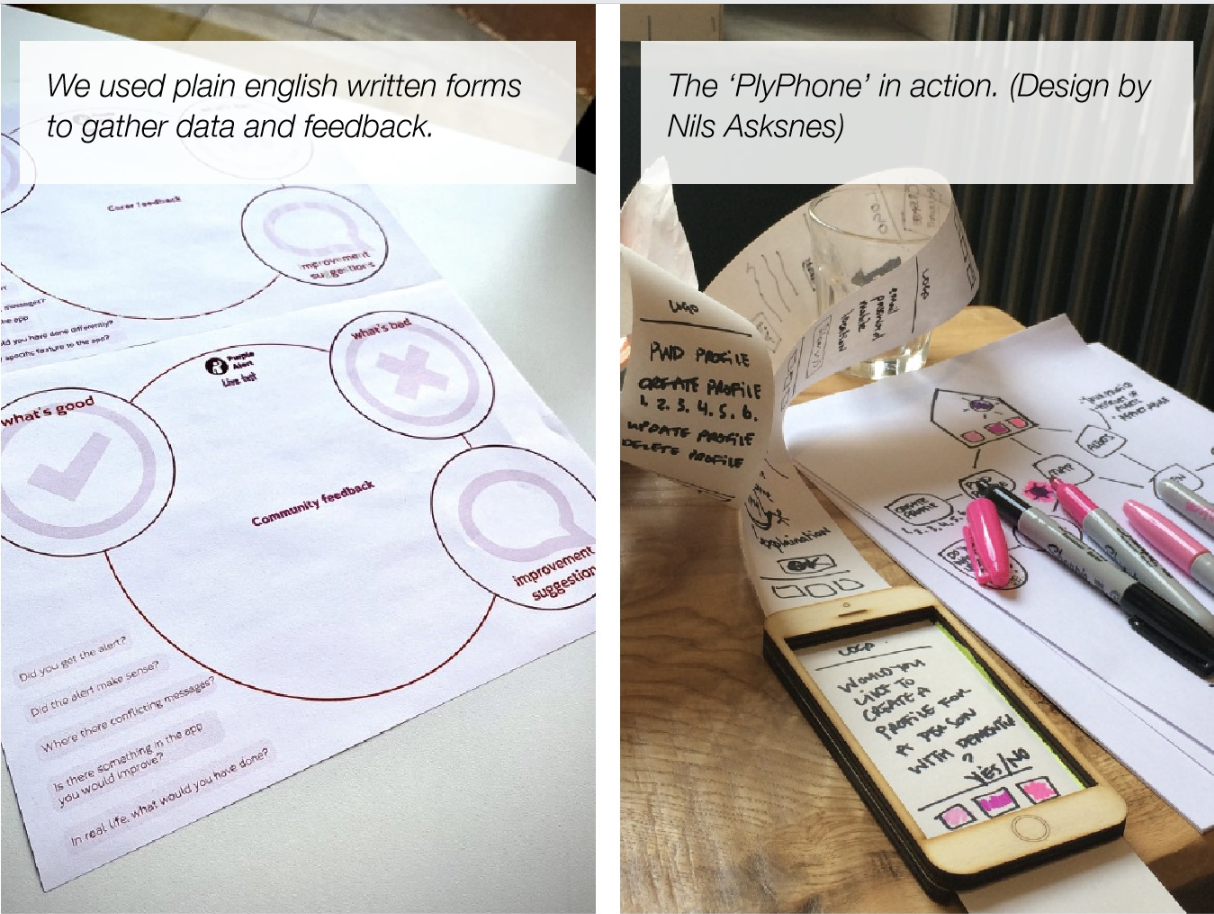

Prototyping a product or a service is fundamental to immediately understand if it’s going to work or not. It doesn’t have to be complicated. In fact, the quicker and more inexpensive it is, the better.

We used Lego figures to recreate scenarios, buildings, people and services. We used a colleague’s “PlyPhone” (a phone made of Plywood) with a till roll to sketch the app interface. We used role-play in the office to work out whether people would behave in a certain way or not.

These simple exercises were fun and saved us lots of time (and resources but made us understand what was realistic and what wasn't, what worked and what didn't.

Live Testing

Only after several mockups of the app and having gathered enough feedback from our steering group we were ready for the app development. We consolidated the brief, broke it down into sections, prioritise them and detailed meticulously the important features.

Coincidentally, in the same period we were approached by an app developer who had already developed a similar app, so we started working together to develop Purple Alert. With the help of the steering group, we evaluated the existing app, but the feedback indicated that it would have made more sense starting from scratch. Developing an app (or any product) from scratch is a lengthy process, especially if it’s ‘one of a kind’.

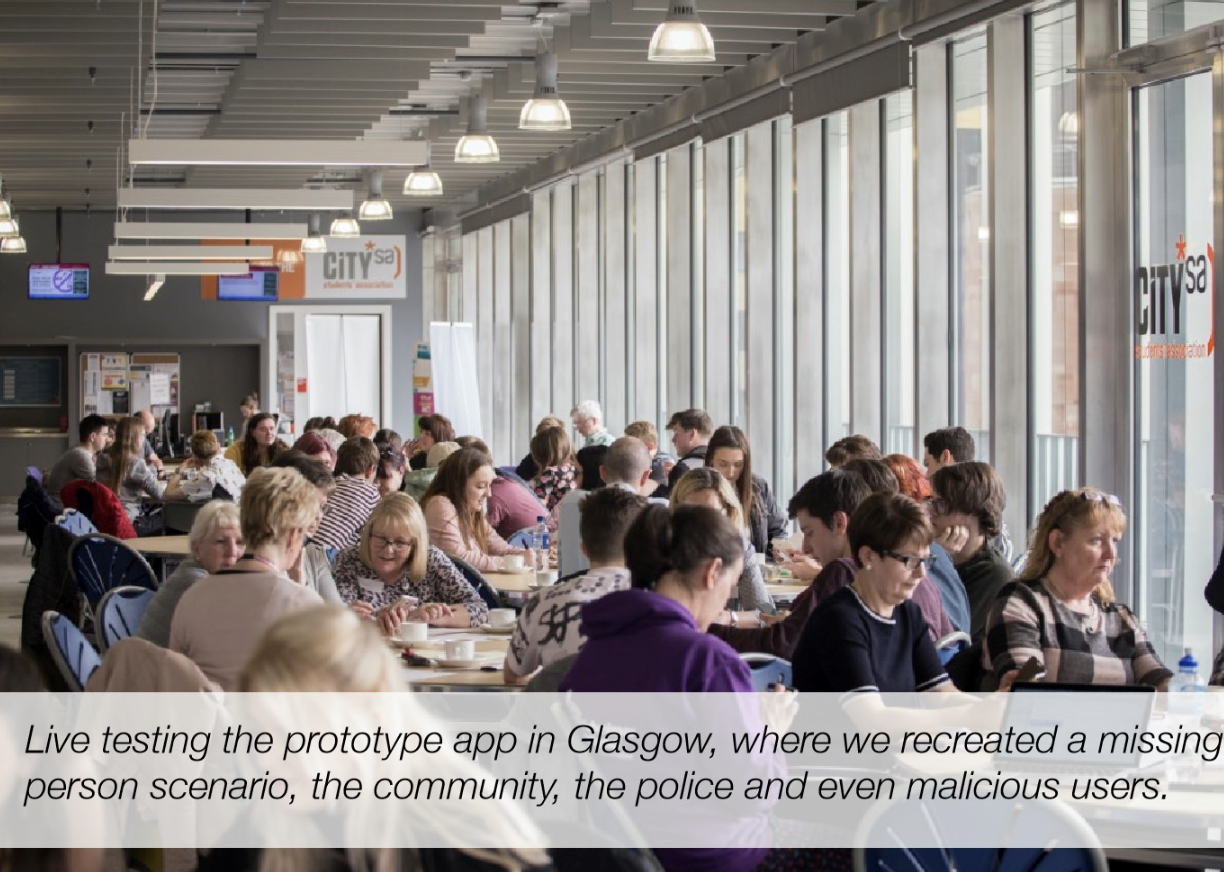

At the time, there wasn’t anything similar we could get ‘off the shelves’ or anything we could learn from, so it was very much a discovery exercise. Within a year however we had our first working prototype. In a similar fashion to rapid prototyping, we tested our first prototype app in three specific settings: in Glasgow with more than 100 testers, in Edinburgh, a touristy city and in Tain, rural Scotland.

These took much more organisation and resources than rapid prototyping, but it was a fundamental learning experience to which we still refer to today. In total, it took us 32 months of service design and product development, 3 live tests and 26 app reiterations before general release. We were confident the product was solid and it would work, but we now had to focus on the ‘buy-in’ from the community: without community, Purple Alert would be pointless, and we didn’t want to run the risk of someone raising an alert, and no one responding.

Live testing

User Journeys

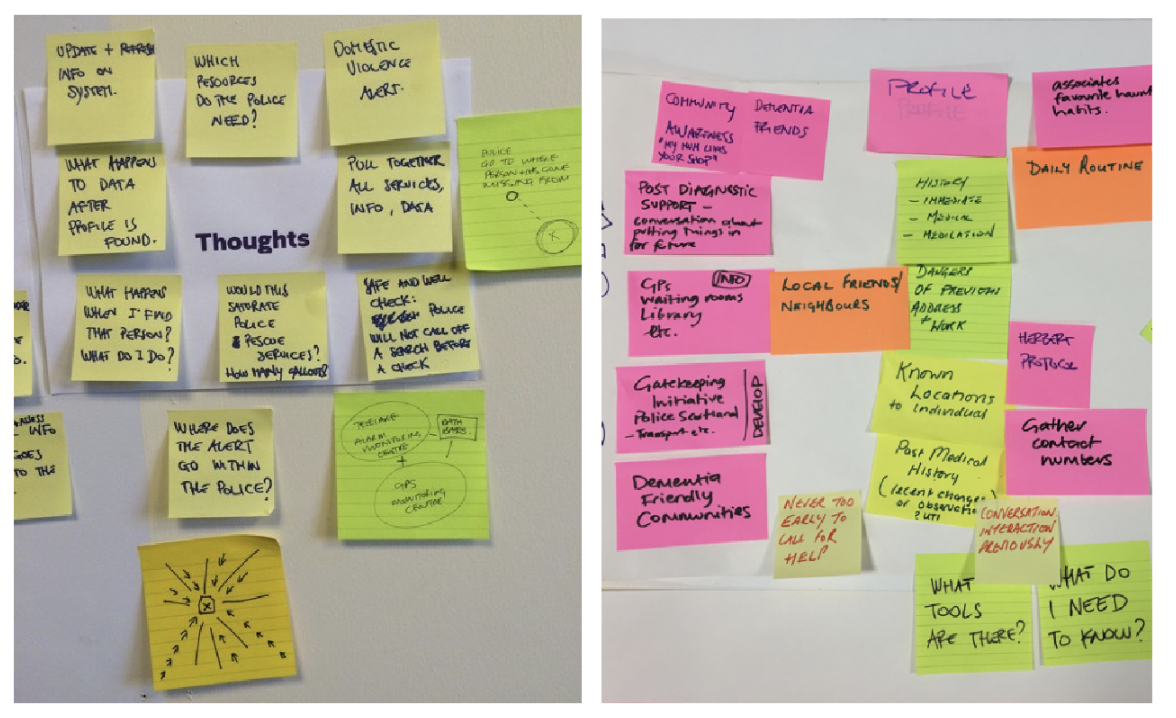

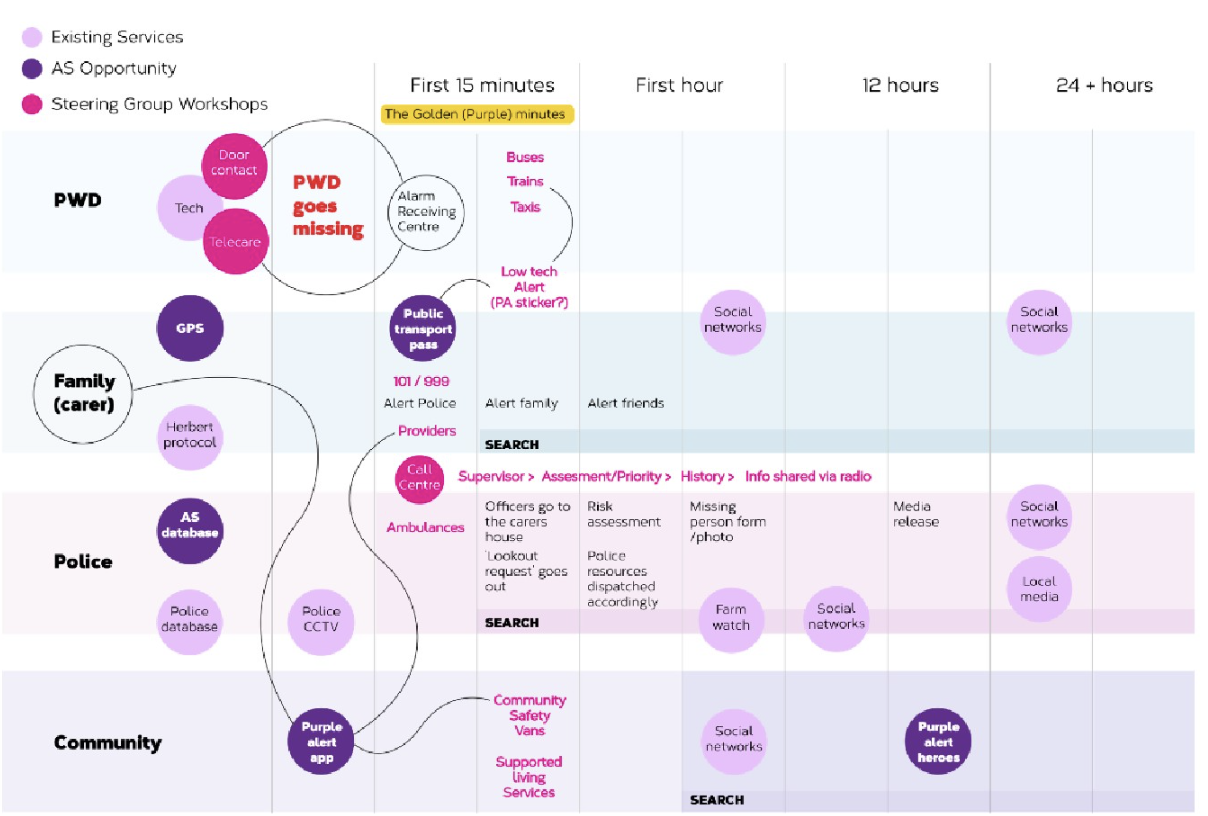

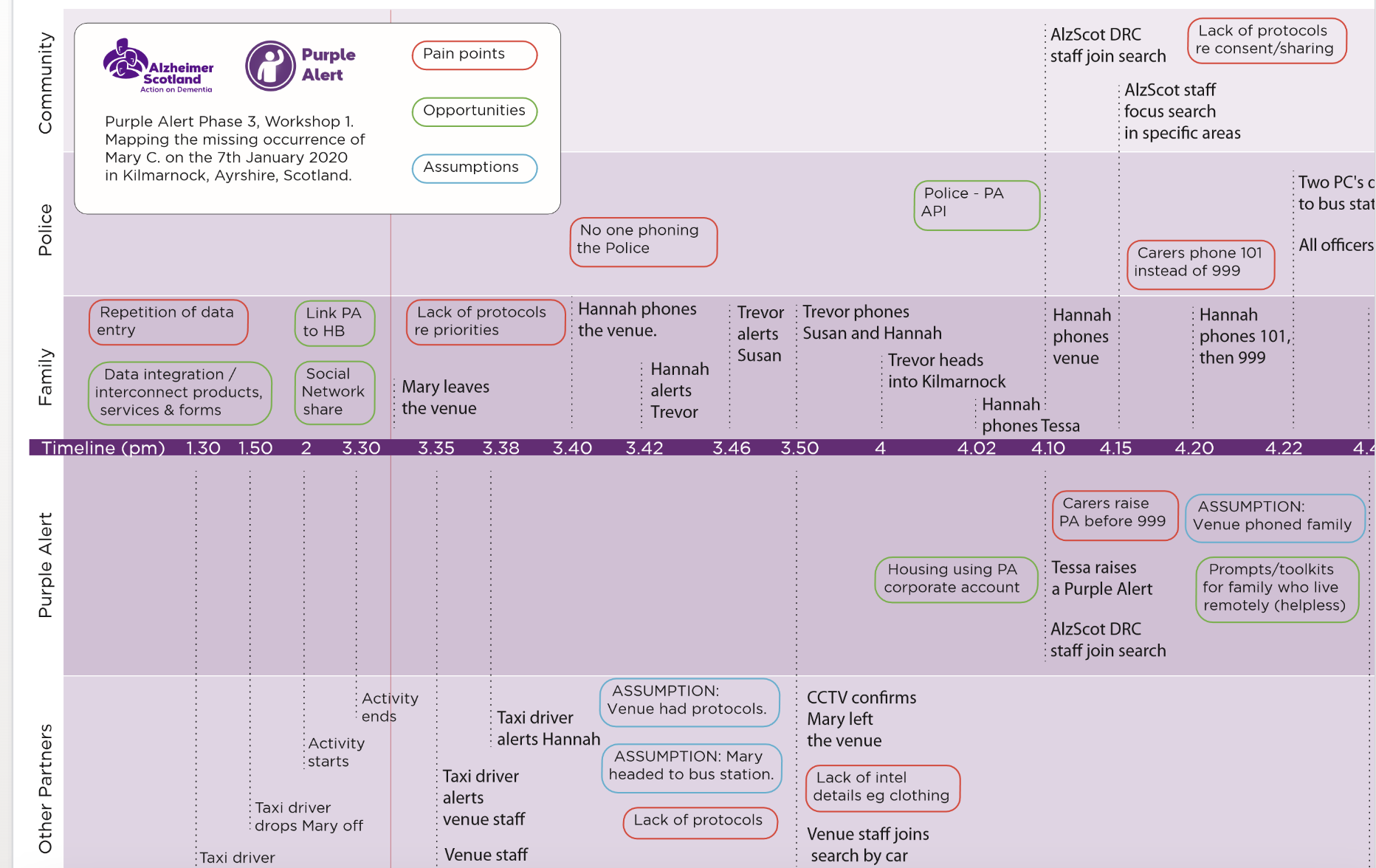

Undoubtedly one of the most useful tools we found from the outset is mapping the user journey of a missing incident from various perspectives. The initial user journeys were drawn on a relatively small timeline, around the moment the PLWD goes missing.

With the help of the steering group we mapped the series of events which occur before, during and after a person is reported missing, the products and services involved and the people who take part in the missing occurrence.

Due to the nature of the project, we also mapped the emotions involved in an incident, which helped us to keep the service “human”, as specified in the brief. By 2017 the initial user journey (right) had become a birds eye view of missing persons services in Scotland (below)

Soft launch

On the 21st September 2017, on World Alzheimer’s Day, we launched Purple Alert. It was a major milestone, but we had to tread carefully in advertising a service which only had about 300 users. We decided to ‘soft launch’ it, and we focused entirely on getting people on board and strengthen the community of users. We called this ‘Phase 2’ and it was as demanding as the initial phase.

We coordinated a massive comms campaign all over Scotland over a period of 12 months, with the aim of reaching at least 4.000 users. We travelled all over Scotland as part of a wider project called ‘Confident Conversations about Technology’ and Purple Alert was integral part of the conversations. We quickly gathered momentum, receiving overwhelmingly positive feedback. The first Purple Alert was raised in April 2018 and in October 2018 it was the first time someone was found thanks to the app. When we saw that the app was used the way we intended and a missing person was reunited with their family, we felt on top of the world. That moment alone was worth all the hard work we put in.

I can’t praise you and any others enough for creating the Purple Alert app as this was an example of how vital it is and I have been advising friends and relatives to download it too.

James, Carer

Learn, redesign, relaunch

By September 2019, we reached 10K users and we had developed a range of services around the app. We designed toolkits for PLWD and their carers about what to do before, during and after a missing occurrence. We produced comms toolkits for communities who wanted to turn their area ‘purple’. We joined the conversation around ‘missing’ with other organisations worldwide, including Academia, Emergency Services, Private, Public and Third Sector.

In Scotland, we participated in steering groups evaluating the National Missing Persons Framework and we joined other teams to shape policies and services around missing and dementia. However, the app we had launched 2 years before still felt like a working prototype. Some features worked very well, some others turned out to be irrelevant and others unexpectedly revealed themselves to be majorly important. The backend of the app was also inflexible and didn’t allow us to measure some key data.

We therefore decided to redesign the app completely, taking into account all we had learned in the previous years. In 2020, in the middle of the re-design process Covid-19 threw in some unexpected challenges which we included in the development process. We very much used the same design tools and the same user centred approach, but with much more experience and know-how.

We relaunched the app on 21st September 2020, exactly 3 years from the original soft launch.

Measuring Impact

When we launched Purple Alert in 2017, we were sure that there was demand for it, but we weren’t sure how much. We were also keen to know how people used the app, when they interacted with it, and if it made people feel safer.

Although we could gather qualitative data from our staff, the communities and the families we support, it was difficult to monitor any quantitative data, since the developers were effectively gatekeepers. When we redeveloped the app, data analysis became high priority in the new brief, and we now have a much better control over both qualitative and quantitative data. We also started collaborating with academic institutions who have all the right tools to analyse our data. By understanding it better, we can focus our work much more efficiently